|

| 1542-1641. Rijksmuseum, CC0, Wikimedia Commons |

“One of Bellarmine’s confreres in the College of Cardinals called him ‘the most learned churchman since St. Augustine’and I’d agree with that,” Fr. Baker[1] said. “His knowledge of Scripture and Theology — he seemed to know the entire Bible by heart, plus the teachings not only of nearly every pope, but of many bishops, too! — it’s just astonishing. Bellarmine was truly a polymath.” [From an interview published in the National Catholic Register in September 2017]

[1] Author of a translation of Bellarmine’s Controversies of the Christian Faith, published by Keep the Faith Books (2016)

The Latin is reproduced courtesy of the Digital Collection site - UANL and is followed by my fairly literal translation. The Scripture excerpts (Douay Rheims/Vulgate) are taken from the DRBO site but the verse numbering follows that of Bellarmine’s Latin text.

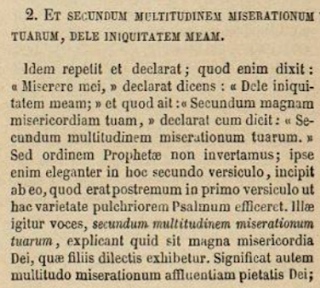

And according to the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my iniquity.

et secundum multitudinem miserationum tuarum, dele iniquitatem meam;

paternal or tender love, which Scripture is accustomed to explain as “the bowels of mercy.” The Church also expresses this most clearly in the collect of the eleventh Sunday after Pentecost when she says: “Who in the abundance of Thy kindness art wont to go beyond our merits and our prayers.” For the divine goodness is truly so great that it not only gives much more than we deserve but also than we dare to hope for. The Lord shows this in the parable of the prodigal son (Luc. xv.) For the father not only welcomed his penitent son back into his grace but, having immediately embraced and kissed him, he gave orders for the first robe and the precious ring to be put on him, and for the fatted calf to be killed in his gratitude. In the end, he showed such great signs of goodwill towards his son (who had dissipated all his goods), that he could not have shown greater had he returned as a victor in triumph over his enemies. What follows, “ Blot out my iniquity,” refers to the guilt and the stain of sins; for David knew, from the effect of sin in his soul, that he had been consigned to the punishment of eternal death; and it had also scarred his conscience with the stain of the privation of grace, and rendered it deformed, darkened and hateful to God. The words “blot out” refer to both. For debts are blotted out when the debt is forgiven; and stains are blotted out when what is stained is cleansed.David therefore asks God not to deal with him in strict justice but, in his paternal mercy to forgive his debt of sin and to wash away the stain by restoring the brightness of grace.

No comments:

Post a Comment